Program 2020

Conference Program

Below you’ll find the schedule for Decolonizing Museum Cultures and Collections: Mapping Theory and Practice in East-Central Europe. We’ll keep this page regularly updated with changes, so be sure to keep checking in!

All times in CEST (GMT+2), Warsaw, Poland Time.

Wednesday, October 21st

3:00 – 5:00 pm Pre-event: Non-European Collections in Polish Museums (Roundtable in Polish)

In this roundtable the Director of the Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw will engage in a conversation with curators from museums of various types (art, city, ethnographic, historical museums, as well as historical residences) on the past and future of non-European collections in Poland. The discussion will cover the following questions: What is the provenance of non-European collections in Polish museums? How is postcolonialism understood by museum practitioners? What are the contacts between museums and representatives of source communities? What are the representations of the figure of the colonial “collector-explorer” in Polish museums? Do they come across questions, accusations, problems related to critical readings of their collections? How was their own professional background shaped? Finally, what are the relations between the museum sector and academia (ethnology, cultural anthropology, art history) in Poland?

The session will be held in Polish.

The Asia and Pacific Museum in Warsaw is our conference partner.

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — —

Moderatorką panelu będzie dr Joanna Wasilewska – dyrektorka Muzeum Azji i Pacyfiku w Warszawie

Paneliści:

dr Lucjan Buchalik – dyrektor Muzeum Miejskiego w Żorach

Katarzyna Nowak – zastępca dyrektora ds. merytorycznych, Muzeum Sztuki i Techniki Japońskiej Manggha

dr Joanna Paprocka-Gajek – kierownik Działu Sztuki, Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie

dr Magdalena Pinker – kuratorka Zbiorów Sztuki Orientalnej, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie

Magdalena Zych – kustoszka Muzeum Etnograficznego im. Seweryna Udzieli w Krakowie

5:30 – 6:00 pm Welcome and Introduction

6:00 – 7:15 pm Decolonial Museology as a Travelling Concept – A Keynote Lecture by Prof. Erica Lehrer, Concordia University, Montreal

7:30 – 8:30 pm Breakout rooms, discussion, networking

Thursday, October 22nd

1:00 – 2:00 pm Curating Polish Patriotism ‘Otherwise’: Queering and Racializing August Agboola Browne (Roundtable 1)

The roundtable is aimed at discussing the recent revival of the story and image of the jazz musician and WWII resistance soldier of African descent, August Agboola Browne (1895 – 1976, nom de guerre ‘Ali’), in contemporary Warsaw. ‘Ali’, son of a Nigerian father and a Polish mother, is believed to have been the only black participant in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. After he left Poland in the late 1950s, his existence was for many decades almost totally forgotten in the city. Recently, his story has returned in discussions of Warsaw’s public history, in part thanks to a series of conspicuous portraits of ‘Ali’ painted in 2015 – 2017 by Polish visual artist Karol Radziszewski. The conversation between Nicholas Boston (sociologist), Magdalena Wróblewska (curator), and Karol Radziszewski himself will focus on two of his paintings from the ‘Ali’ series that were purchased by the Museum of Warsaw and then exhibited sequentially in its new core exhibition “The Things of Warsaw”: one depicted a naked black man against a white-red background recalling the Polish national flag (2017 – 2019), the other showed a black man dressed in a Polish insurgent army uniform (2019 – ). Radziszewski’s portraits of ‘Ali’ helped the museum uncover hidden entanglements between the city’s wartime past and the (post)colonial imaginary, by questioning well-established patterns of collective memory focused on a homogenous, white Polish society, and challenging its military idioms. At the same time, curatorial practices surrounding both paintings, along with memory activism performed in urban space and on social media, catalyzed a pluriverse of interpretations among visitors. The symbolic meaning and social impact of the rediscovered figure of ‘Ali’ will be discussed from the perspectives of the artist, the museum curator responsible for displaying the portraits, and the media scholar who explores them with a critical queer lens.

Panelists’ abstracts:

Nicholas Boston

Portraying Ali: A Queer Eye on the Black Guy

This paper explores the depiction of the black male subject in the production and exhibition of representational art, particularly portraiture, in contemporary Poland. The central case study through which this discussion will be launched is a series of portraits by the artist Karol Radziszewski that depicts an historic figure somewhat obscured in the narrative of Polish resistance, August Agboola Browne. A Nigerian-born jazz musician, Browne, through his involvement with the resistance movement, served in the Warsaw Uprising, being the only known black combatant in the Uprising. He went by the code name, “Ali.”

Mr. Radziszewski is openly gay, and has described himself as Poland’s first openly gay or queer contemporary visual artist. His practice is multimedia and he is well known for his installations challenging heteronormativity (in Polish society). Radziszewski’s archive-based methodology crosses multiple cultural, historical, religious, social and gender references. As the queer media scholar Łukasz Szulc has written, Radziszewski’s work is highly reflective of Polish history and driven by an ethos of reclamation of silenced or submerged queer Polish histories. This artistic practice has involved the exhibition of actual archives of photographs and other artefacts.

Foraying into painting, Radziszewski created the series “Ali (2015 – 2017).” One of these portraits “found his place in the permanent collection of the Museum of Warsaw that opened last night,” Radziszewski announced in a post on Instagram on May 24, 2017. The selected portrait, which depicts Ali as a shirtless young man with massive, bulging musculature, bears no resemblance, beyond race, to the archival photographs that exist of Browne. The real Ali was 49 years of age at the time of the Uprising, once married to a Polish woman and father of two children; in every photographic representation, he is slight of build and fully clad in suits and ties.

Controversy over the Ali portrait ensued, as observers remarked that Radziszewski’s portrayal is contradictory in not only its representational elements, but by consequence, its exhibition. Immediately surrounding it on the wall of the museum are, in the words of one commentator, portraits of “white Polish men looking dignified in their military uniforms.” In stark contrast, Radziszewski’s Ali is literally stripped bare, a spectacle to behold. “This is really a queer eye on the black guy,” another observer expressed. (These comments are drawn from social media and informal conversations.)

A transnational discussion took place about the hyperphysical, and what many perceived to be sexualized, depiction of this man of African descent and the extent to which Polish cultural producers undertaking representations of non-western, particularly Afro-diasporic, peoples and identities (dis)engage with a politics of difference in the conceptualization of their work.

This paper, then, is a sociology of art production that deploys analyses of race and sexuality. It first draws on interview data from an in-depth interview conducted with Mr Radziszewski, discussing issues such as artistic traditions and discourses (one strand of the debate concerned the artist’s composition of Ali in a style reminiscent of Picasso, and whether that decision uncritically replayed an appropriative, western relationship to African aesthetics and material culture).

The paper then turns to the question of intersectionality to probe whether a queer/gay aesthetic has here misarticulated racial subjectivity.

2:30 – 4:00 pm Curatorial Dreams from (Polish) Museum Outsiders (Roundtable 2)

Engaging in a conversation with multicultural scholars and practitioners, this roundtable will explore how Polish historical, ethnographic, and art museums look from the perspectives of diverse communities of Poles. As museums are important tools for shaping collective memory, we will also consider new possibilities and practices for broadening the historical and cultural imaginaries our national museums present, towards a more inclusive future. In short, we ask: What is the status quo in Polish museums? What are the “curatorial dreams” of Poland’s marginalized communities? What would it take to make them come true?

4:30 – 6:00 pm Histories of Collecting (Paper Session 1)

This presentation seeks to uncover the role that Polish ethnographers, scientists, explorers, and others played in the collection of colonial artifacts and the reproduction of colonial knowledge by focusing on the works of Leopold Janikowski and Jan Czekanowski. By studying their interest and engagements in the colonial world, I seek to understand the significant place that colonies had for Polish national agendas and the role that museums, exhibitions, and the act of collecting itself had popularizing colonialism in Central and Eastern Europe. My overall goal is to analyze the cultural and political tensions surrounding colonial artifacts and the status that these had for European nations and empires more broadly.

Franz Binder Museum from Sibiu, Romania, is the only “universal ethnography” museum in the country, even if scattered extra-european collections are hosted by other museums, as well. Under reorganization procedure since 2015, the museum faces the challenge to propose a more relevant message to its public, a challenge doubled by a potential “representation crisis” due to the fact that it is part of ASTRA National Museum Complex, an ethnographic institution presenting communities from Romania in their traditional dimension. Even if this region has never been a colonial rule overseas, I argue that not only the colonial dimension is embedded in the way museum’s initial collections were formed in late 19th and early 20th century, but also that this very dimension is something that has curatorial potential as the objects themselves, regardless of their intrinsic value. As a case study on one of the museum’s collections I propose to analyze the ways and the context in which the Franz Binder collection was formed – even if one out of many, this collection also gives the name of the museum. The objects were collected and brought in Sibiu from Binder’s voyages up the shores of the White Nile, an uncharted territory back in the 1860s. Received in Sibiu with great enthusiasm by the Transylvanian Society for Natural Sciences, as a “gift made by a prince”, the curatorial approaches of this collection so far, owned by several museums in Sibiu since its donation, have ignored as irrelevant the very condition of its formation. Since it was formed around the same time that anthropology was born as a science, I also analyze the relationship between postmodern anthropology and the world cultures museum from Sibiu, in the perspective of its reopening.

In 1973 the Nusantara Museum was founded in Warsaw, renamed in 1976 for today’s Asia and Pacific Museum. Its founder Andrzej Wawrzyniak was a diplomat and member of communist party, collector and traveler, creating his image and persona as an explorer of exotic countries. In that time a private collection transformed into a public one gained an interest of the broad audience and an important feedback in the period’s media. When analyzing the collection and archives, we can see today how – in post-colonial time, non-colonial country and anti-colonial political context – a quasi-colonial narrative was created, presented and accepted, shaping and confirming at the same time views of the audience. Museum’s early activities focused strongly on exoticism, aesthetic values of collection and adventurous collecting process.

Today, we face the new challenge creating a new and first in the Museum’s history permanent exhibition. For years already, a new generation of curators works for change of the “mysterious East” vision, too long in use. However, given our experience and educational needs, we decided for traditional, geographical construction of the display, called “Journey to the East”. Then, we want to indicate for the fact that the collection and its history mirrors a Polish/European gaze directed to the East. We want to focus on cultural diversity and complexity of the major part of the world, traditionally described as “Asia” even if, as Tokimasa Sekiguchi wrote, Asia does not exist. On the textual level, we also want to draw the visitors’ attention to the context in which collections were created and perceived. The accompanying program, especially educational activities, should also include the reflection on Western and specifically Polish attitudes toward foreign cultures and their heritage.

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) functioned as a third way between the two blocs, aiming to creatively contribute to the existing world order. It advocated for peaceful coexistence, disarmament, territorial integrity, and supported anti-colonial struggles. Different collaborations and exchanges were established between non-aligned countries in the field of economy, business, education and culture. Yugoslavia as one of the founders of the NAM participated in those processes which significantly contributed to acquiring new museum collections from other continents.

Slovenia was one of the six republics of former Yugoslavia at the time, and its foreign policy importantly influenced the field of museology. In 1964, the new Museum for non-European cultures was established as a branch of the Slovene Ethnographic Museum (SEM). It was filled with collections from all over the world which were the result of museum curators’ fieldwork, collaboration with amateur collectors and foreign students, artists’ donations as well as donations from the Presidency of Yugoslavia. Between 1960 and 1990, over 80 exhibitions were organized, among them nearly half traveling exhibitions from non-aligned countries. In 2001, the Museum for non-European cultures was closed and all the non-European collections were transferred to the SEM.

Together with ethnographic museums from all over the western Europe, SEM has recently been part of two EU projects that deal with colonialism and decolonization of museum practice. According to its specific history and museum practices from the second half of the 20th century that were marked by NAM principles of solidarity and friendship, the museum curators developed collaborative approaches with heritage holders to share the responsibility of interpreting their heritage. This was an experiment on developing new strategies and visions of collecting and interpreting non-European collections in the SEM on the basis of specific anti-colonial disposition from the time of the NAM.

During the “migrant crisis” of 2015, several commentators pointed to the difference in attitudes between Western Europe and the “former” Eastern bloc towards foreigners. In Eastern Europe, the absence of a colonial and immigration past would explain the difficulty of confronting racialised otherness. Irrespective of whether this East-West distinction is justified or not, the reasons given raise the question of why certain experiences of encounters and confrontations are ignored. However, the societies of the people’s democracies have been in contact with this immigration, particularly in the framework of the international solidarity of the communist bloc.

By focusing on Poland and especially in the case of Lodz, this contribution aims first to show that the presence of “Third World” students under communist rules has permeated the daily life of the population, but that this legacy has been broken after 1989: the “Bloc” no longer existed, academic networks were oriented to an European whiteness (Law and Zakharov, 2019) and the colonial question was forgotten. Secondly, I would like to show how this forgotten history could be turned into a legacy. Some academic research, conferences and exhibitions have already carried out on foreigners in Polish cities. The question arises as to how to present in museums and outdoors several objects (works of art and administrative forms), places (student hostels and clubs) and testimonies not as remnants of an exotic past, but as testimonies of a shared memory. Finally, the question of this colonial presence also raises questions about the national past, the opportunities and constraints of living in state communism.

6:30 – 8:00 pm Histories of Exhibitions (Paper Session 2)

The authors’ interest to revising the role of Museums of Mankind or Man disseminated around the world between the 1920s and 1980s aligns with current attempts to redefine various implications of physical anthropology as embedded into global history of race science. Ann Fabian (2010)1, Britta Lange (2011)2, Alice L. Conklin (2013)3, Samuel Redman (2016)4, Tony Bennett et all (2017)5 brought into analytical and critical lenses the legacy of anthropological collections in Vienna, Paris and Washington in order to emphasize the mission of the museums as signifiers of racism aimed at practicing the power of ‘whiteness’ as hierarchy through materially representing otherness and bringing about colonial reductionism.6 We explore critical historical reflection of anthropological collections in terms of Bhaskarian critical negation or non-identity, intention to emancipate from the views and practices stemmed from physical anthropology. We map the critical narratives concerning physical anthropology as pending between transformative negation targeted at emancipating prominent achievements of anthropology from its false ideologies, and radical negation aimed at deconstructing European identity seen as a universal, multifaceted platform for physical anthropology.

The development of physical anthropology in Eastern Europe including the culture of museums should be seen as a part of adapting the main Western pathways for translating ‘whiteness’ and the hierarchy which supports ‘whiteness.’ Established in the early 1920s in Prague, the Museum of Man is one of the most consistent examples of such adaptation until nowadays. Aleš Hrdlička, a famous American physical anthropologists of Czech origin, directly supervised the development of Czech physical anthropology and provided solid material support for elaborating the Museum’s collections. We reconstruct history of the Museum as an adaptation of Western, primarily, American and German models of anthropological museum or “repetition without replication”7 and shed light on the role of the Museum in legitimizing physical anthropology during different periods of Czech history.

1 Ann Fabian The Skull Collectors: Race, Science, and America’s Unburied Dead left off (Chicago, 2010).

2 Brita Lange Sensible Sammlungen in Margit Berner, Annette Hoffmann, Britta Lange (eds.) Sensible Sammlungen Aus dem anthropologischen Depot (Hamburg Philo Fine Arts: 2010): pp.15 – 40.

3 Alice Conklin In the Museum of Man – Race, Anthropology, and Empire in France, 1850 – 1950 (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 2013).

4 Samuel Redman Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums (Harvard University Press 2016).

5 Tony Bennett, Fiona Cameron, Nélia Dias, Ben Dibly, Rodney Harrison, Ira Jacknis, and Conal McCarthy Collecting, Ordering, Governing: Anthropology, Museums, and Liberal Government (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

6 Tony Bennett “The exhibitionary complex” New formation 1988, 4 pp. 73 – 102: p. 80.

7 Linda Hutcheon A Theory of Adaptation (London New York Routledge: 2006): p. 7.

Museums of natural history, world cultures (formerly and sometimes still known as ethnographic museums), anatomical and medical museums hold bodily remains from ancient but also more recent history. They are traces of past lives and bear witness to the livings relationship to the dead but also to remaining structural unequal power relations. Departing from an ongoing long-term collaboration with colleagues from the Natural History Museum Vienna (NHM Vienna) and the research project TRACES1 (Transmitting Contentious Cultural Heritages with the Arts. From Intervention to Co-Production), this paper analyzes how the human story of these bodily traces, incites new ways of research methodologies based on interdisciplinary (artistic, ethnographic, historical,…) approaches, and can be opportunities for transmitting difficult (imperial/colonial) heritages. How can the collective but also personal engagement with collections of human remains evoke changes in present institutional structures, foster future collaborations and build new relationships? Can it contribute to deconstruct (neo)colonial systems that are lingering on? What are the ethical implications in engaging with these collections – Some individual’s remains at the NHM Vienna were collected under violent and ethically questionable circumstances. To shed light on this collection’s histories, the paper unravels how Viennese collectors of the 19th and 20th centuries were entangled in the networks of the Imperial (Mapping and categorizing the inhabitants of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) and Colonial Project (Collecting and classifying human crania from overseas). Stressing Vienna’s function as a center of knowledge transfer with easy access to human corpses2 between Eastern and Western Europe. The paper focuses on examples from a series of creative-reflexive public engagements with the NHM’s human remains collection. By doing so, it discusses if and how the analyzed formats can contribute in building ethical-reflexive and decolonial futures.

Among rich collections of different provenance kept at the Museum of Man in Wrocław (Poland), there are 80 human skulls acquired by German comparative anatomist and physical anthropologist Hermann Klaatsch (1863−1916) during his fieldwork in Australia (1904−1907). The paper is an introductory intervention into the topic, aimed at presenting how the call for decolonizing in the museum sector may refer to museum objects kept in a country such Poland that did not have its own colonies. As the museum is closed since March 2020 due to the COVID-19 restrictions, the presentation will be focused on reconstructing the history of the Klaatsch’s collection and providing the contemporary international context which may affect its future. This story addresses both the global approach to engaging with colonial pasts as well as Poland’s historical particularities connected with the aftermaths of the Second World War.

This paper presents and discusses an artistic intervention conducted by Karolina Grzywnowicz in the Botanic Garden of the Jagiellonian University in July 2019. The intervention was a result of an art&research residency during which the artist spent two weeks in the garden, accompanied by a research team, discovering the history of the institution, observing the way it functions, conducting interviews with its employees and discussing her observations during open meetings held in the garden.

Grzywnowicz’s intervention took a form of a contrfactual, alternative guided tour. It was the artist’s response to the colonial structures of organising knowledge and exhibiting nature that she observed in the garden. The two crucial notions for this tour were, on one hand, the clear divisions between ‘native’ and ‘exotic’ (and value that is attributed to each of the categories); on the other hand — the peripheries, both of the topography of the garden itself, but also as a position from which the discourse of the institution is being constructed and reproduced, in relationship to the ‘center’: former colonial empires and botanical institutions that resulted from their colonial explorations.

8:15 – 9:15 pm Breakout rooms, discussion, networking

Friday, October 23rd

1:00 – 2:30 pm Reframing Europe (Paper Session 3)

Rural heritage often appears as “out of history”, locked in pristine folkloric collections or unspoiled open-air museums. This presentation takes a critical anthropological approach to knowledge production about rural material culture in East-Central European museums. The paper uses the examples of “folkloric” objects as openings into the exploration of global encounters and difficult local knowledges locked in museum collections. It addresses the historical context of two museum collections to interrogate the complex provenance of rural objects within the ruptured histories and charged socio-political landscapes.

Firstly, the case of textiles held in the Horniman Museum in London demonstrates how folklore collections emerged from the difficult past of rural collectivization and deprivation, and how acts of exhibiting traditional museum artifacts across the Iron Curtain served to create certain representations of the modern state. Secondly, the collections of the Museum of European Cultures in Berlin (MEK) highlight the ways in which an anthropological insight can help unlock unconsidered histories and shed light on the manifold political relations that underpinned the movement and display of these artifacts. Through these examples, the paper provides a reflection on the potential of decolonial approaches to the study of rural collections residing in ethnographic museums, paying particular attention to the possibilities afforded by anthropological and historical methods.

By addressing questions of acquisition, movement of objects, their local context of dispossession, and their political performance, the paper challenges the perceived ‘neutrality’ of East-Central European folkloric material and the categories of ahistorical ‘ethnographic regions’ in which these collections have been acquired. Rather than presenting Europe’s people without history, rural objects have a capacity to uncover unconsidered histories, processes social transformation, and displacement of East-Central European rural communities, as well as providing a window into the political lives of objects. These perspectives can point to new avenues for changing museum cultures representing rural heritage.

The European Capital of Culture is considered a success and a ‘brand’ of the European Union. It became a dominant policy paradigm for how culture, memory, and heritage can be articulated – and sold – in European cities. After EU enlargements to Central and Eastern Europe, ‘modernization’ and ‘Europeanization’ appeared as one of the primary aims of the programme, alongside the usual aim of developing the city and region. Sibiu’s tenure as ECoC in 2007, the year of Romania’s accession to the EU, put forward the multicultural and multiethnic history of the city in which Romanians, Saxons/Germans, Hungarians and Roma lived together peacefully, while emphasizing the German heritage of the city and the contribution made by Saxon colonial settlers to the city’s heritage at the expense of other heritage or urban forms. Romania and Sibiu signalled Europeanization and ‘return to Europe’ through the valorization of Saxon Settler Colonialism and German heritage. Museums operate(d) within a culture underpinned by what I call ‘monocultural multiculturalism’ characterized by a hierarchization of ethnicities and heritages within European cultural policies and urban development strategies such as the ECoC. As such, institutions such as the Lutheran Church and the Brukenthal Museum benefited from the ECoC, while other museums that did not fit with the narrative of urban German history such as the ASTRA museum (an open-air museum dealing with Romanian rural life) were disadvantaged within the programme. In this presentation, I will focus on contemporary heritage-making practices in Sibiu, Romania, while placing these transformations within the broader history of German colonization to the East, Austro-Hungarian empire, and post/socialist transformations of Romanian Saxon cities. I will interrogate what these perspectives from the ‘margins’ of postcolonial EUrope illuminate about Europeanization, heritage-making processes, and museum cultures.

Established by the Hapsburg colonial administration of Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1888 as a cultural epicenter for the newly acquired province to collect and proliferate anthropological, archaeological, and historical knowledge production and analysis of the population of Bosnia, Zemaljski Muzej served as an educational institution aimed at forging a post-Ottoman Bosnian national identity. Like most other colonial museums, Zemaljski also collected, classified, and showcased the natural history and mineral resources of the province. It became an important tool in inventing, structuring, and synchronizing pre-Ottoman Bosnian identity with European history. Through its own periodical, Glasnik Zemaljskog Muzeja, the museum historicized and curated a Bosnian national identity while also creating a collective memory of an imagined shared past of all peoples living in the territory of Bosnia. This presentation focuses on the coloniality of Zemaljski Muzej and looks at social movements emerging around its post-socialist and post-war reconstruction. Specifically, I look at the struggles of museum employees to keep the museum running through the Ja sam Muzej (I am the Museum) campaign, an initiative which resulted into the gradual morphing of the museum itself into a site of contention and one in which past and present political grievances were mobilized towards the engendering and articulation of new forms of dissent and solidarity.

Read more on The Politics of Postcolonial Erasure in Sarajevo by Piro Rexhepi: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1369801X.2018.1487320

As Rebecca Jinks has recently argued, mainstream depictions of the Bosnian genocide in literature, art and museums of the former Yugoslavia have served to ‘replicate the representational framework of the Holocaust’. 1 Relying heavily on concentrationary imagery and neat categories of victim and perpetrator, Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) writers and artists drew on, and at times appropriated, Jewish suffering during the Holocaust years to legitimise their own experiences of systematic violence and persecution at the hands of Croatian as well as Serbian forces in Bosnia and Herzegovina from 1992 – 1995. Yet these post-Yugoslav memory cultures, into which Jewish experience has paradoxically been subsumed, further marginalised the suffering of Bosniak victims by perpetuating a western European view of genocide as an exceptional, modernity-defining and exclusively concentrationary event. This paper examines the recent initiative of Galerija 11/07/95 – the first memorial gallery in Bosnia- Herzegovina – to commemorate the 25 th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre, in which 8,000 Bosnian Muslims were murdered, in conjunction with the Holocaust. As part of this initiative, the gallery publicly invited ‘all museums, galleries, cultural and other similar institutions’ to participate in the multidirectional memorialisation of the Bosnian genocide by installing the Bosnian photographer Tarik Samarah’s 2004 artwork ‘1945 – 1995 – 2020’ on ‘the exterior or interior of the museum/building in the form of a billboard, poster or photo projection’. 2 Showing a mother from Srebrenica apprehending an image of Anne Frank and her sister outside the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, Samarah’s photograph links the respectively Jewish and Bosniak victims of mid- and late-twentieth century genocide, yet does so via invoking a central figure of western European cosmopolitan memory. In the paper I investigate Galerija 11/07/95’s initiative as an example of the ways in which post-Yugoslav museum practice in Bosnia has attempted to resist the colonial memorial structures of western Europe, and consider the extent to which these efforts successfully represent the distinct genocidal experiences of Jewish and Bosnian Muslim minorities.

Rebecca Jinks, ‘Representing Genocide: The Holocaust as Paradigm?’, S.I.M.O.N. – Shoah: Intervention. Methods (2018) 2,

54 – 71 (p.67).

2 ‘A photo-historical mise en abyme: mother of Srebrenica outside the Anne Frank House’, Galerija 11/07/95, 10 June 2020

<https://galerija110795.ba/a‑photo-historical-mise-en-abyme-mother-of-srebrenica-outside-the-anne-frank-house/>

[accessed 1 st October 2020]

3:00 – 4:30 pm Reframing Africa (Paper Session 4)

The ECHOES Project focuses on the history of colonialism to collectively reshape and give voice to merged colonial memories and multicultural expressions. These memories and expressions are at the heart of contemporary heritage debates, within and beyond Europe. In this context, researchers from Work Page 4 Entagled Cities have been analysing the way cultural traces and identities related to musealised heritage from the African presence are being managed by the National Historical Museum in Rio (Brazil) and National Museum of Ethnology in Lisbon (Portugal). Both museums have collections related to colonial history and an African presence in their respective cities. These collections can tell us about the dissonant dimensions of this history, in order for society to understand the origins of multi-ethnic identities, the hybrid dimension of these cultures, and a multiplicity of forms of inhabiting space, without denying the rich diversity of cultural roots. In this light, both museums are using different understandings of concepts of multiculturality to work with their collections to develop their educational programs and pedagogical tools.

This study has viewed the museum as a “culturemaker”. Not only does a museum act as a key element in the interpretation and collective uses of these cultural heritages, but it is also a powerful educational space to inclusively manage identity conflicts, seek consensus, and build democracy. Given this preface, the following research questions have guided this study’s path: How and by whom are these collections being de-codified, interpreted, and communicated? Have these heritages been repressed, removed, and reframed? Or are they re-emerging with a renewed and powerful role in current societies, so that they can be key elements for empowering subaltern memories? Are these museums helping to erase ethnic, racial, or cultural stereotypes and their multiplicities of sociocultural violence?

One of the most famous collections of foreign artifacts in Poland is presented in the National Museum in Warsaw. The Faras Gallery, originally accessible since the 1960s and reopened in 2014, exhibits the precious finds from the Faras Cathedral in Nubia discovered by Kazimierz Michałowski. Michałowski stands out as one of the most prominent archaeologists in Poland. The Nubian Campaign (1961−64) conducted under the aegis of UNESCO was the milestone in Michałowski’s career. His scholarly achievements resulted in acknowledging his role as the founding father of the Polish Mediterranean archaeology.

Thus, the Faras Gallery in the National Museum in Warsaw displays not only the Early Christian past of Nubia but also the successes of the Polish school of archaeology. The narrative constructs the image of Polish scholars as innovative and internationally recognized for their skills and abilities. The recent study by Lynn Meskell (2018) conducted in the archives of UNESCO proves that the story behind the Nubian Campaign is different from the narrative presented to the wide audience in Warsaw. Monumentalized and mythologized achievements leave no place for the negative and colonial aspects of the Nubian Campaign.

In my presentation, I hope to shed light on the parts of the Nubian story that were hidden on the display. To interpret the new exhibition, I will use the term, “negative heritage” coined by Meskell in 2002 and place my considerations within the critical heritage studies. By discussing the fragmentary and colonial character of the museum narrative, I aim to deconstruct the myth of Faras in Polish archaeology. Unveiling the negative character of Nubian heritage in Poland will set a starting point for offering a potential decolonizing scenario for the exhibition.

In my paper I would like to focus on a genre of museums which is rarely discussed, especially in a political context: historical house museums. These museums, usually created in homes previously inhabited by historical figures, often are seen as strictly aesthetic, without an ideological agenda, and thus are rarely analyzed through the lens of critical theory. I would like to focus on two Polish historical house museums which can be analyzed in the colonial context. The first one the Henryk Sienkiewicz museum in Oblęgorek. Henryk Sienkiewicz was a Polish journalist and novelist awarded with the Nobel Prize. He is known, among others, for his travels, which he described in his published travel essays and which inspired his book In Desert and Wilderness. This novel is criticized by many anthropologists for representing a strictly colonial point of view and for picturing Africans as inferior to Europeans. The second museum is the Arkady Fiedler Museum in Puszczykowo. Fiedler was also a traveler and writer. He not only wrote about his travels, but also was connected to the political groups striving for the creation of Polish colonies. In my paper I would like to discuss how this legacy of colonial fantasies, present in the works of both Sienkiewicz and Fiedler, is represented in historical house museums devoted to these writers.

There is a new problem in relations between African countries and the West connected with the restitution of ethnographic and art objects plundered during colonial period. It has great significance for museums, their collections, strategy of exhibitions. However, Polish collections are not carrying a stigma of robbery and violence. Poles in Africa usually used to be teachers, engineers, doctors or missionaries. During their African residency they gathered objects buying them or getting as gifts. The State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw in its new exhibition is going to stress the cooperative attitude of Poles and present objects with well-documented provenance. Furthermore, the strategy of building collections in The State Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw bases on taking objects from Polish collectors like Bojarscy Family from Nigeria or Krystyna Jankowska from Democratic Republic of Congo. The strategy besides practical matters addresses two important issues. The first one underlines the role of Polish collectors in the world African art market. The second one gives an opportunity for the museum to broaden knowledge about the acquisition of objects such as masks, fetishes, weapons by interviews.

5:00 – 6:30 pm Critical Curating 1: Acting Locally (Paper Session 5)

It seems that over the centuries too many mistakes and misreadings of Roma art have been committed by scholars, historians, art curators, journalists, and ordinary people – all wishing to understand it. Probably the most far-reaching and historically burdened mistake was to ethnographize and – in consequence – self-ethnographize the art of the Roma which for many years was described and analyzed by ethnographers only. As such, the Roma were colonized and presented as naïve artists, amateur artists, primitive artists and their work was usually associated with folk culture. This state of affair has been changing for the last couple of years; also in Poland where professional artists of Roma origin and Roma contemporary art have finally emerged. Today over a decade has passed since 2007, when the first Roma pavilion was set up in Venice. Private and state-owned art galleries increasingly often organise international exhibitions of contemporary Roma art, while Roma artists are invited to display their works at exhibitions focused on other themes. Also, Roma artists themselves initiate multiple artistic events. Based on my own curatorial experience with regard to contemporary Roma art in Poland, I would like to address several questions concerning institutional visibility of Roma artists in nowadays Poland and in the Polish art world, themes addressed by artists and their art, and the long journey from colonised folk makers, as they were widely seen, to decolonised contemporary artists, what they are today.

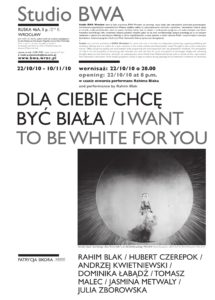

The presentation will discuss the exhibition which took place a decade ago in Wrocław, at Studio BWA (22 October – 10 November 2010) and accompanied the conference organized, under the same title, by the Institute of Art History at University of Wrocław. It was a reflection on ethnic, religious and national distinctness and the possibility of cultural dialogue in a homogeneous society, with emphasis on contemporary Poland. The exhibition included the works of artists who, in their work, explore that issue at varying levels. The following artists from diverse cultural, artistic and generational backgrounds were invited to participate: Rahim Blak (Krakow), Hubert Czerepok (Wroclaw), Tomasz Malec (Lublin), Julia Zborowska (Krakow / Vienna), Andrzej Kwietniewski (Lodz), Jasmina Metwaly (Poznan / London / Cairo), Dominika Łabądź (Wroclaw). The title I WANT TO BE WHITE FOR YOU was taken from the refrain of the song sung by Reri – a beautiful dark skin star from Tahiti who appeared in the Polish film “Black Pearl” in 1934. From today’s perspective her performance in the film does not fall within any framework of political correctness. The title, inspired by the song and the backstage history of the heroine, is symbolic – it provokes a consideration of how to evoke egalitarian dialogue between the minority and majority, on coexistence and cohabitation, which would result in a synergistic effect of enrichment on both sides instead of damaging dependence. Reri’s utopian desire to become white with bright eyes and unite with her white ideal, is replaced with the utopia of a harmonious existence “next to”. Questions about the preservation of cultural identities of ethnic minorities present in Poland, and about tolerance and openness of Poles to others are still valid. These problems are presented not only by the multicultural artists but also by Polish artists who are careful observers of changing realities.

While working on the permanent exhibition at The Asia and Pacific Museum, we realised how much Poland has changed in the past ten years. Traveling around the globe has become easier more accessible. Teenagers visit Asia during vacations with their parents. Twenty-year olds choose Bali over Italy as their holiday destinations. We started asking questions about their perception of the world, Museum’s collection, objects from Asia and Pacific and decided to invite this new generation to a project called “STIRRING”. In 2019 and 2020 students from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and the University of Warsaw (Institute of Art History) participated in various workshops and discussions. They met with curators, conservators and cataloguers, visited Museum’s storerooms and created their own pieces that were inspired by the Collection or commented on it. In the process we discovered what issues are crucial and most interesting for young people, what they search for in the museums of world cultures, what is their attitude towards them and how to meet the expectations of the first generation that lived their whole lives in a globalised world.

Long-term artistic collaborations have proven to be very useful tools in curatorial practices. In this paper I would like to present the method adopted in programming such collaborations using projects STIRRING (PORUSZENIE) and THIS IS POLAND / THE ASIA AND PACIFIC MUSEUM (TU JEST POLSKA / MUZEUM AZJI I PACYFIKU) as case studies.

Exhibitions are available at wystawa.muzeumazji.pl and muzeumazji.pl/wystawy czasowe/tu-jest-polska

Can a curatorial reuse of a well-solidified piece of cultural heritage reveal the work’s critical potential to address the concerns East-Central European societies are facing today? To which extent can postcolonial and postcommunist experiences meet when faced with issues of race and identity? This presentation will address these question on the base of Halka/Haiti: 18°48’05″N 72°23’01″W, a project the author curated for the Polish Pavilion at the 56th Venice Biennale, in 2015, in collaboration with the artists Joanna Malinowska and C.T. Jasper. Halka/Haiti involved staging the Polish national opera Halka (1858) by Stanisław Moniuszko in Cazale, a Haitian village inhabited by descendants of Polish soldiers who had fought for Haitian independence in 1803. The project probed the relevance of 19th-century European artistic forms for the representation of national identities in a complex postcolonial context. The work was subsequently included in the collection of Zachęta — National Gallery of Art in Warsaw as well as the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC.

C.T. Jasper and Joanna Malinowska, in collaboration with Magdalena Moskalewicz, Halka/Haiti: 18°48’05”N 72°23’01”W, 2015. Soloists from The Poznan Opera Theater

and audience during the performance in Cazale, Haiti, February 7, 2015. Photo: Damas Porcena (Dams), Haiti

7:00 – 8:30 pm Diverse Perspectives from Implicated Communities (Roundtable 3)

Since East Central Europe (ECE) did not have its own overseas colonies, there has yet to be sustained conversation on the relevance of “the colonial” to museums and other heritage sites in the region, and there has – to our knowledge – been little attempt to connect with source community members to consult about the treatment and interpretation of relevant collections and sites. Paired with a session where “internal” local representatives of minority groups in Poland discuss how they would like to engage with and be represented by museums, this session offers a window onto the experiences of individuals representing “source communities” – as well as those with more tangled connections of affinity, adjacency, or proximity – who have worked with museums and heritage in other parts of Europe. A key goal is to help ECE practitioners understand the possibilities and anticipate the challenges of engaging with the full range of communities relevant to the multiple, relational histories of their sites or collections.

The topics we will explore include: the practical, political, and person challenges and benefits of trying to gather and curate the knowledge, relationships, and emotions that diverse community members bring to collections that implicate their cultural groups; the value of using arts-based practices for illuminating and presenting collections; questions of collaboration, dialogue, and the different vectors of teaching and learning as knowledge about objects is produced.

Panelists’ abstracts:

Carine Ayélé Durand

Decolonising collections: a renewed dialogue with the originating cultures for fair exchanges

The Ethnographic Museum of Geneva (MEG) is resolutely engaged in a proactive process of decolonising its practices and the history of its collections. An assumed and committed decolonial approach represents a real challenge in a country that did not have colonies as such, but which nevertheless has a rich and complex colonial history. MEG aims to demonstrate that decolonisation concerns all countries, regions and institutions whose citizens have pursued colonial practices, sometimes even after declarations of independence. With this in mind, MEG wishes to sensitize its audiences and partners on the colonial roots of its collections, the knowledge it has produced and its museology. The general objective is to engage, from our Swiss and European reality, a translocal dialogue and fair exchanges with the descendants of those who were colonised. This dialogue is based on three foundations. The first is to shed light on the history of the Museum’s collections by deepening our knowledge of the provenance of the objects, in particular their motive and the way in which they were acquired. The MEG will undertake to inform culture carriers of the presence of sensitive objects in its collections. The second is to re-establish the link between “source communities”, from the five continents, and the collections or archives that concern them, with the aim of reappropriating their heritage. The point here is to gather around the collections in order to strengthen the voices of the descendants of those who created the Museum’s objects, to co-construct new knowledge and new interpretations. The third is to promote exchanges with artits and artisans, with the aim of generating new artistic creations, and to encourage researchers, but also culture bearers and audiences to look to the years to come and work together to shape a decolonial future.

Rado Ištok and Léuli Eshrāghi

Placing Slovak Collections into Great Ocean Relationality

In this presentation, Rado Ištok and Léuli Eshrāghi chart the first ocean-going outrigger vessel between the colonial collections of Ancestral Belongings in Slovakia and the many Indigenous archipelagos of the Great Ocean where they originate. Unpacking the prestige, racial bias and epistemic violence implicated by creating ethnographic museums in the 19th and 20th centuries in Slovakia and East-Central Europe, we place these long languishing collections back into constellation with Indigenous communities and diasporic/migrant contemporary artists whose capacity to reinterpret and remedy these collections is salvatory and necessary.

Through understanding the historical context which shaped the establishment of non-Western ethnographic collections in Slovakia in the periods of the New Imperialism (1880 – 1914) and Global Neoliberalism (post-1989), Ištok’s current research considers potential ways of ‘unlearning imperialism’ (Ariella Azoulay) in the present and near future. Ištok’s research further develops methodologies for anti-racist curating of the region’s non-Western collections in the near future, grounded in an understanding of their role in the past.[1] Together we conduct research into Great Ocean collections in the Slovak museums in Bratislava, Košariská, Piešťany, and Martin, as well as Vienna, Budapest, and Prague, with a particular focus on barkcloths.[2]

Eshrāghi will discuss recent artworks made in response to barkcloth and Ancestral Remains collections in museums in Europe, Turtle Island and Australia, particularly the performance paper/s/kin (2018) and the series of mnemonic animated barkcloth or siapo viliata that starts with TAFA (((O))) ATA (2020).[3] In dialogue with other artists and researchers working across the Great Ocean, Eshrāghi will provide an understanding of the Ancestral Belongings’ meaning for Great Ocean cultures and create an artistic response to the poorly researched collections in Slovakia.

[1] Understanding the role that non-Western ethnographic collections played in the past is crucial for imaginaries of multiple futures. How are we to acknowledge the presence of the non-Western collections in Slovakia without reproducing a Western-centric museum of world cultures? How do we curate the collections in a context which is, unlike the metropolises of Western Europe, largely homogenous, with very small migrant communities and restrictive immigration and asylum policies? Engaging with heritage from their regions, contemporary artists could, in part, compensate for the lack of experts on non-Western collections in Slovakia.

[2] See e.g. Peter Mesenhöller and Annemarie Stauffer, eds., Made in Oceania. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Social and Cultural Meanings and Presentation of Oceanic Tapa Cologne, 16 – 17 January 2014, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2015.

[3] These works comprise new writing, moving image and animated drawings reflecting on Indigenous futurisms, data sovereignty, non-colonial museology and community-driven cultural memory initiatives in the Great Ocean and its diasporas. The second in the series can soon be accessed at Subspace.art and the third, AOAULI (2020), through ACCA’s platform.

8:45 – 9:15 pm Breakout rooms, discussion, networking

Saturday, October 24th

1:00 – 2:30 pm Critical Curating 2: Thinking Globally (Paper Session 6)

The context of semi-peripheral countries such as Poland adds new layers to the understanding of (post)-colonial history. How to grasp the region, which was both oppressed and oppressor? Based on two exhibitions curated by Joanna Warsza at SAVVY Contemporary in Berlin in 2017 and at La Colonie in Paris in 2019 the talk will casts a light on how colonial and neocolonial forces have navigated the territories of Eastern-Europe, Poland in particular, through a choice of artworks. From Emma Wolukau-Wanambwa’s “Paradise” (2012), where artist looks at the remains of a refugee camp of Poles in Uganda during the Second World War and the relations between the erased memory and the all-visible documents testifying to the unfulfilled hegemonic aspirations; to today’s perverse use of postcolonial theory in the nationalist agenda in the work of Agnieszka Polska. Such an inquiry can offer ways to better understand the region’s right-wing turn, the permanent need of affirmation of its exeptionalism and victimhood, the lack of the critical examination of its own imperial past, but also the feeling of discrimi¬nation in Western Europe. Those exhibitions were meant to offer ways of going beyond such entanglement, also with the help of artificial intelligence in the work of Janek Simon.

To decolonize museums first we should decolonize the collective memory. Before 1989 socio-political change, the Polish People’s Republic global economic contacts were closer with so called “Third World” (now called Global South), then with the West. Curating vast archives of this historical collaborations shows how the official government agreements lead the way to unexpected, unofficial, even illegal links. This the case of Polish-Indian “friendship” as shown in the exhibition “Prince Polonia”, but also of Polish engineers working in Arab countries and Arab students in Poland, as shown in performative lecture “The suits that we have in our country are not suitable for the tropical climate”. These two art projects (different versions of display in Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Clark House Initiative in Bombay, Trafo in Szczecin and performance at Biennale Warsaw) prove that socialist “Second World” ambiguous position had many advantages.

The paper introduces the concept of our research exhibition, which includes archival materials and contemporary works of art — film and photography — to be presented at the third edition of OFF-Biennale Budapest in spring 2021. The OFF-Biennale Budapest is part of the East Europe Biennial Alliance of contemporary art biennials based in Budapest, Prague, Warsaw, and Kyiv. The exhibition looks at the historical relationships and parallels between the global periphery (Global South) and semiperiphery (Eastern Europe) during the 20th century through the concepts of coloniality, peripherality, and migration in a multi-focal perspective. Can Hungarian settlers in Latin America, Cuban migrant workers in Hungary, and Afro-Asian students in Eastern Europe have a common history? How did people in these regions, seemingly divided by various boundaries, perceive, interact with and shape each other? Is there a shared colonial history of Eastern Europe and the Global South? The decolonialist agenda of the Transperiphery Movement is to question and decenter history dominated by the global center from the perspective of the global peripheries, by recentering peripheral positions and their interperipheral relations. It seeks to understand the global history of Eastern Europe and the Global South through their shared peripheral experiences: dependency on the center, relation to coloniality, as well as emigration and being afar. The exhibition aims to transform our spatial understanding of the world through re-learning history in translative movement between peripheralized positions to uncover their transformative interconnections.

More about the project: https://offbiennale.hu/en/2021/projects/transzperiferia-mozgalom

3:00 – 4:30 pm Holocaust and Decoloniality (Paper Session 7A)

Until recently, Russia had not remembered the Holocaust as a unique evil in twentieth century history. This was true both in the Soviet Union and in an independent Russia. However, this position has changed markedly since Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012.1 A specific Holocaust memory has now developed in the Russian Federation, one which emphasises “Soviet heroism, the fascist leaning of former republics and contemporary Russia’s supposedly tolerant, multicultural society in which the most painful periods of history are confronted”.2

This paper addresses this phenomenon by examining the temporary exhibition “Шоа-Холокост. Как человек мог сотворить такое?” (Shoa-Holocaust. How could a person do this?”), displayed in 2018 at the Museum of Victory, Moscow3, but curated by Yad Vashem.4 The Yad Vashem exhibition is available in twenty-one languages, but the Russian version of the exhibition is different to the other versions that could be accessed online (English, Spanish, Hebrew).5 It seems that the Russian version was rewritten and repackaged for a specifically Russian audience, and this paper will highlight the distinctiveness of the Russian version, including the topics that only the Russian copy confronts. It will also examine the tensions between the understanding of the Holocaust in the West and the Russian interpretation of events as presented in the exhibition.

This paper will use this case-study to showcase a unique memory-culture that is developing in the Russian Federation, one that has been critically overlooked in the West and that is part of a broader engagement with Holocaust memory by ethnonationalist partners in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. It will highlight the specific elements of this uniquely Eastern Holocaust memory, one that exposes, problematises and deconstructs the Holocaust memory practices of the West.

2 Ibid.

3 ‘Shoa-Kholokost. Kak chelovek mog sotvorit’ takoe? [Shoa-Holocaust. How could a person do this?]’, Muzei Pobedi <https://victorymuseum.ru/exhibitions/in-the-hall/vystavka-shoa-kholokost-kak-chelovek-mog-sotvorit-takoe-/> [accessed 22 May 2020].

4 ‘Shoa-Kholokost. Kak chelovek mog sotvorit’ takoe? [Shoa-Holocaust. How could a person do this?]’, Yad Vashem <https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/ru/exhibitions/ready2print/index.asp#shoah> [accessed 22 May 2020].

5 ‘SHOAH. How was It Humanly Possible?’, Yad Vashem <https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/ready2print/index.asp#shoah> [accessed 22 May 2020].

New Polish historical museums, founded and developed within the recent “museum boom”, usually don’t carry a direct burden of their own colonial past or troublesome collections that need to be processed. However, they produce memory forms that are often embedded in problematic visions of the past that can be unpacked with the aid of post-colonial and post-dependence studies: these celebrating Polish national perspective as a default one, as well as these picturing Poland as an innocent victim of history.

This memory type obviously simplifies the story of Poland being colonised in the 19th century, and is blind to the history of Poland as an “internal European coloniser” as well as her complicated attitude towards minorities. To discuss intricate relations between these dependencies and oppressions, I examine museums that can serve as examples of maximum implication: situated in the regions of complicated German-Polish histories, connected with political oppression, cultural struggles and forced migrations, constantly negotiating their position between the regional memories and the national identity.

Recently opened permanent exhibition of Upper Silesian Jews House of Remembrance in Gliwice adds one more layer to the story. While this museum in a pre-war German, post-war Polish city adheres to a discourse of pluralism, acknowledging the German past of the land and providing a state-of-the-art presentation of Jewish community history, it can also be tempted to frame the story of persecution as “alien”, someone else’s heritage, placing Polish community in a relatively comfortable position of a contemporary host of the land who has yet nothing to do with its darker historical chapters. Balancing between the strategy of “othering” both Germans and Jews and this of establishing multidirectional bonds with their histories, Gliwice museum is a striking example of post-dependence implications and so will serve as a central case of my talk.

The presentation is dedicated to two archival exhibitions showed in the Regional Museum in Tarnów and curated by Adam Bartosz: Gypsies in Polish Culture from 1979 and Jews in Tarnów from 1982. Although ethnographical in principle, both expositions covered also the topic of genocide and tragic fates of Polish Roma and Jews in the 20th century. Based on archival materials documenting the two shows and interviews with the people engaged in their production, the presentation investigates visual imageries and regimes of representation of Roma and Jews that they employed from the perspective of global Holocaust memory and postcolonial reflection. What had been the means of rendering the Shoah and the Romani genocide before the main Western paradigms of commemoration were established? What were the affinities and differences in representing Romani and Jewish fates at these two exhibitions? What are the intersections of local and global memory of the Holocaust? Can we discuss non-Western ways of representing the Shoah and the Romani genocide? And how to approach the exoticizing representations of Jews and Roma on the grassroots level from the postcolonial perspective?

3:00 – 4:30 pm (Post)Communism and Decoloniality (Paper Session 7B)

This paper is based on the conviction that “another type of knowledge is possible” (Stoler 2016) but must be created “beyond the northern epistemologies” – (Sousa Santos 2008). I will not focus on “the darker side of western modernity” like Mignolo (2011), but on a positive example of “border thinking” (Mignolo 2000); in this particular case a critical theory based on Second-Third World assemblages and some discursive-non-discursive approaches. The aim is not to reconstruct the history of the Second-Third World relations. I have already done that in my book Socialist Postcolonialism (2018). The purpose is to create a methodological framework based on a shift from First-Third World relations (the dominant subject in postcolonial studies) to Second-Third World relations. The visual arts will be treated as an illustration of the paper’s theoretical part and as an artistic expression of politically engaged critical studies. I will take a closer look at the role of non-discursive critical tools used in art. The problem is, to what extent difficulties with the conceptual framework as such, understood as part of Western discursive hegemony, can be solved in the non-discursive language of art (with some of the trans-historic dialog between Polish socialist artists and Vietnamese contemporary critical art, like the Propeller Group)? Maybe we should rather ask what sorts of not-only-discursive practices – visual arts, performance, dance, or theater – are or at least could be an alternative solution to post/colonial Western dominance?

This presentation will discuss how the current protests in Belarus have transformed and re-arranged the system of historical and cultural references that shaped the foundation of Belarusian collective memory and identity discourses since 1994, which centred on two segregated but co-existing martyrological projects – the official discourse focused on the memory of the victims of fascism, and the oppositional discourse focused on the memory of victims of Stalinism. During the 2020 protests, these previously disconnected and competing historical narratives have blended and integrated as a result of memory work aimed at supplying symbolic means of making sense of the new experience of political violence. Presentation will discuss the case of the Museum of Great Patriotic War in Minsk and its symbolic role in the spatial dynamics of the Belarusian protests in August-September 2020.

Thirty years after the collapse of USSR, the establishment of Soviet rule and its consolidated continuance remains an inevitable part of the memory discourse in independent Armenia. Hypothetically, on the national level Soviet heritage was posited as undesirable and often obscured. Positive contradictory narratives related to the past are maintained on the local level though. Moreover, it is assumed that official institutionalized memory in Post-Soviet Armenia was strongly intercorrelated with earlier forbidden memory of Diaspora Armenians. Thus, Soviet heritage in Armenia and the memory of the past 70 years were marginalized and, in radical cases, tabooed and forcibly forgotten. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to examine interrelations between state-driven memory politics and local memories. As such, the principal research question of the proposed paper is stated as follows: how do institutional state-driven memory narratives interrelate with the forms and content of local museums and contextual public realms of memory? Additionally, the question of how the Soviet heritage is represented on the local and national level is examined. Methodologically, tools of political anthropology are implemented through interviews, observation, and in-depth semiotic analysis and positioned as the main methods. Collected data is analyzed comparatively in the aim of tracing the process of reconstruction of mnemonic structures related to the Soviet heritage. In theory, the paper is based on the memory studies framework in the context of the anthropological and semiotic analysis of the political center-periphery division. Researched material consists of local museums juxtaposed with national museums, serving to contextualize realms of memory within central and peripheral circumstances.

Dealing with colonial histories in Eastern Europe necessarily means unsettling hegemonic narratives. Zooming in on regional nuances complicates these narratives and requires analysing the local level relationships between different imperialisms that define the contours of social, political and cultural processes in the region. My presentation will map curatorial practices that engage with the histories of scientific racism in the Baltic region, researching these histories both within and in collaboration with museums. My particular focus will be on two exhibitions that bring to the fore colonial entanglements in the processes of regional history-writing. “Shared History” (2018) at the Art Museum Riga Bourse curated by Inga Lāce involved new works by artists Tanel Rander and Minna Henriksson as well as curatorial research into American Indonesian-expert of Latvian origin Claire Holt presented in a newly-developed video. “The Conqueror’s Eye: Lisa Reihana’s In Pursuit of Venus” (2019) curated by Kadi Polli, Eha Komissarov and Linda Kaljundi at the Kumu museum showed the artist’s large-scale video installation previously representing New Zealand at the Venice Biennial also involved a critical investigation into the imperial engagements of the Baltic German and Imperial Russian pictorial legacies. The two exhibitions have brought along an important shift in understanding the impact of imperial histories in the region and beyond it by critically investigating the participation of local researchers in imperial forms of knowledge production. Furthermore, they have also started the process of interrogating their meanings for the local museums’ archives.

The presentation is aimed to provide a general overview of state of affairs in Ukraine in dealing with colonial Soviet heritage in museums, public space, and cultural institutions. The presentation tends to provide an understanding of the controversies of the local processes and acknowledgment of the audience with the main actors of the local cultural scene. In the case of dealing with colonial heritage in Ukraine, it is rather hard to limit ourselves to museums, as long as public and media space (printed media, radio, television, and cinema) were as much important for Soviet propaganda, as actually museums in their classical form. What raises discussion today is mainly solid – it is either monuments or architecture that through the shape and its decoration still manifests former Soviet statements. Social realist paintings almost fall out attention, they are just placed in a context of overall historical narrative.

Decommunization was launched officially in May 2015, when President Poroshenko signed four laws on the subject. In 2017 Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance informed that 1320 monuments to Lenin had been removed. Due to privatization that took place after the Soviet Union breakdown, many buildings that carried ideological meaning in terms of their architectural form and decoration with mosaics, murals, and stained glass currently are in private property and owners renovate them according to own taste – Soviet symbols also vanish in capitalistic competition by its own.

As long as there is no state intention to museificate Soviet heritage, “decommunization” is criticized by some of the local artists, art critics, curators and activists that allocate themselves “on the left” and initiate projects, on contrary aimed at the preservation of decommunized objects, however many of such projects are reminiscent and nostalgic rather than present objective scientific analysis of former Soviet that should be historicized as any other colonial artifact.

5:00 – 6:00 pm ECHOES Reports: Exploring and Practicing Decoloniality in Museums

In this presentation, we will report on the results of the collaborative project on city museums carried out in Amsterdam, Warsaw and Shanghai between 2018 and 2020. In short, our research identifies how ‘decolonization’, a notion that has excited global interest and action, differs – regionally, nationally, locally. The cultural memory of Amsterdam as a historic colonizer poses different challenges to decolonizing the museum than the forgotten entanglements in the overseas colonization in the case of Warsaw. Shanghai museums show sharply that decolonization does not necessarily involve ‘critical’ discourse as conceived by critical museology. Moreover, both Warsaw and Shanghai add complexity to what decolonization can mean beyond the memories of overseas colonization. Overall, decolonization in museums and the associated debate have evolved in a number of different regional directions and are likely to develop in divergent ways in future. The research was funded by the ECHOES project (Work Package 3) and has resulted in several reports and publications by associated researchers.

Discussion on a draft of Practicing Decoloniality: A Practical Guide with Examples from Museums by Csilla Ariese (University of Amsterdam) and Magdalena Wróblewska (University of Warsaw/Museum of Warsaw), a book written as one of the outputs of the ECHOES Project. The book discusses six aims of decolonization of museums, namely: creating visibility, increasing inclusivity, decentering, championing empathy, improving transparency, and embracing vulnerability.

Authors write in their introduction:

In essence, decolonization is denormalization. Although there are no easy or uniform answers on how best to deal with colonial pasts, this collection of practices functions as an accessible toolkit from which museum staff can choose, experiment, and implement according to their own needs and situations. The book is divided into six chapters, each of which focuses thematically on one aim of decolonization. Each chapter begins with an essay in two parts, which describes what the particular challenge is of decolonizing according to that theme and then follows this up by describing ways in which change can be approached. Furthermore, each chapter contains four practical examples from museums around the world.

During an online meeting, Csilla and Magdalena would like to discuss with you the idea behind the book and to hear your suggestions for further examples or readings that would be of benefit to future readers.

If you wish to read a draft of the book, please contact us: echoes@is.uw.edu.pl

6:30 – 8:00 pm Decolonizing Museums: A Global Perspective (Roundtable 4)

In this final session, a range of theorists and practitioners will share their views on key issues and challenges that characterize the current debate on museums and decolonization, as seen from their diverse regional and disciplinary vantage points. What trends can we observe on a global scale? What are the regional peculiarities? What ideas, experiences, and concerns, and wisdom can these thinkers share with East-Central Europeans?